An adjustable rate mortgage seems like a good idea, but when interest rates start to rise, you’re going to regret your choice.

This past week, the Federal Reserve raised its benchmark interest rate by three-quarters of a percent.

The last time the Fed raised interest rates by that much was in 1994. To give you some context of how long ago that was: back in 1994, the top song of the year was Ace of Base’s “The Sign”, and you could actually go to the airport and meet your friends and family at the gate.

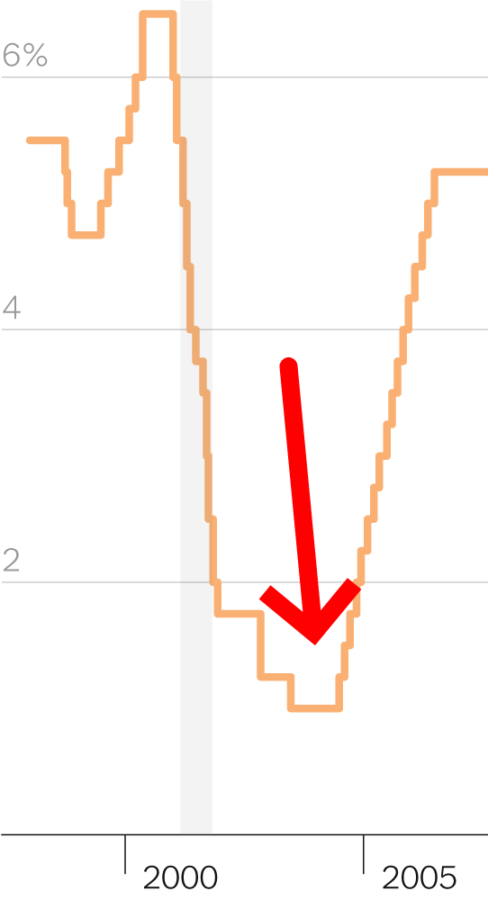

It’s so far back that when the New York Times put up the above graph, it didn’t even bother to go back that far.

But so what? Are interest rates related to high prices? (No.) Are high interest rates related to house prices? (No.) Are high interest rates related to mortgage rates?

No. But yes. Let me explain.

Table of Contents

Mortgage rates and interest rates

Interestingly, mortgage interest rates aren’t actually directly tied to benchmark interest rates.

As the New York Times puts it:

“Rates on 30-year fixed mortgages don’t move in tandem with the Fed’s benchmark rate, but instead track the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds, which are influenced by a variety of factors, including expectations around inflation, the Fed’s actions and how investors react to all of it.”

You would be forgiven for not particularly caring about the distinction. After all, 30 year mortgage rates have almost doubled this year, from a little over 3.0% in January to a little under 6.0% now.

For whatever reason, treasury bonds or something else, rates are going up. I’m not a better, but I wouldn’t bet on them coming down any time soon.

Adjustable rate hell

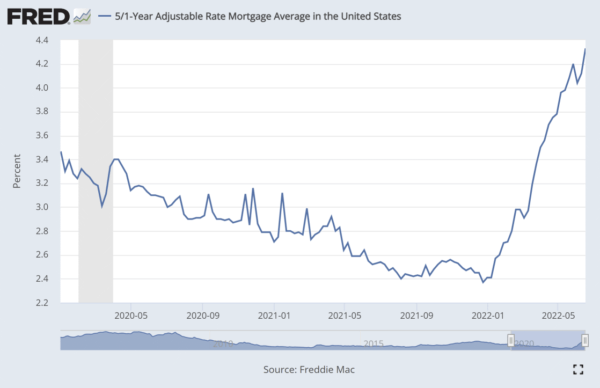

An adjustable rate mortgage (or ARM) is a mortgage whose interest rate can change over time. Often it’s fixed for a few years, and then can float around. The standard is the 5/1 ARM, which is fixed for the first five years of the loan, and then adjusts every year after that.

The advantage here is that the initial interest rate on an ARM is comparatively lower than a fixed rate mortgage, so it often looks more attractive to homebuyers.

Now, look at this graph of 5/1 ARM rates, and you tell me what’s happened this year alone.

That’s right, the interest rate has almost doubled too. Except that with an ARM, and unlike a fixed-rate mortgage, this affects you now, even if you got the mortgage years ago!

This means that more money is going to be taken from you every month from now going forward. Whenever that interest rate rises, your monthly mortgage payment goes up.

And depending on the size of your mortgage, a single percentage point could be hundreds of extra dollars each month.

This is hell. You are strapped into the worst roller coaster ride of your life, and you are riding in your home. The only way to escape is to sell your home, or refinance.

Why you don’t want an ARM

The reason why you don’t want an adjustable rate mortgage is because when interest rates rise, you will have to pay more, perhaps lots more, and there’s nothing you can do about it.

The other reason is stress. You don’t know when or if interest rates will rise, so you don’t know by how much your payment will change. You’re not in control, you’re just along for the ride.

Now, by comparison. I’ve made a quick chart of the interest rate I’m paying on my home.

Sure, it was a higher than an ARM when I got it, but that is no longer true. And it’s not just about the money, it’s about certainty. In a world where prices change frequently (and not for the better), a fixed rate mortgage can offer you certainty and dependability. How much is that worth to you?

Same thing goes for private student loans

This one is personal.

Because while I’ve never had an ARM, for almost a decade I had private student loans. And private student loans have the same problem: floating interest rates.

The school I was going to at the time wasn’t a traditional school, and so it wasn’t eligible for federal student loans. So private student loans were my only option. Hello Sallie Mae!

So what was the problem? Well, the first problem was, the only private loans offered were adjustable rate, meaning that if interest rates rose, my rate would rise in lockstep with them.

The second problem was: that is exactly what happened.

Let me zoom in on this part of the graph of interest rates. I will point out exactly when I took out $15,000 in student loans.

It’s not difficult to see the issue here. Every few months after that point, the fed raised interest rates, and I would get a letter from Sallie Mae stating that my monthly payment, already challenging since I was living in New York City, would be increasing.

And increasing.

And increasing.

It was a scary time, and I didn’t know how long it would last. Would interest rates head up to the 20% range, like they had in the 1980s? What would I do then? I’m certain I wouldn’t have been able to afford that.

Luckily, two things happened:

- The 2008 financial crisis brought the economy to a standstill, and interest rates went into a freefall.

- I got sick and tired of having “good” debt, and put all my energy into paying it off.

I don’t ever want any of you to have to go through that kind of stress ever. So, if there’s any way for you to do not get a variable interest rate loan of any sort, please, just don’t.